By Giridhari Das

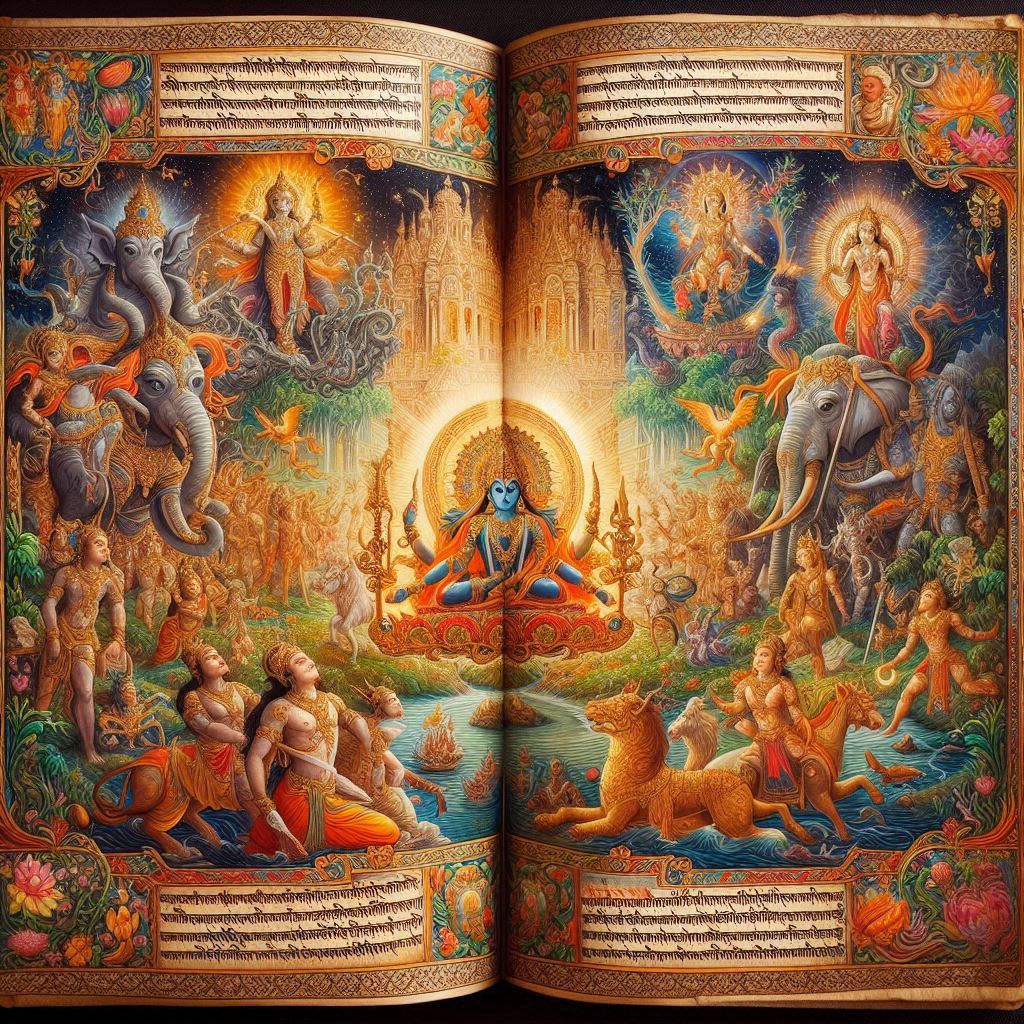

Bhakti-yoga, as explored in my book The 3T Path, is the most joyful, powerful, and intimate process of spiritual connection with God. Rooted in the ancient tradition of yoga, this path stands out for its essence based on love—the most natural and universal force we all carry. Unlike practices that may seem distant or inaccessible, bhakti-yoga transforms every action into an expression of devotion and bliss. In this text, I highlight three fundamental aspects: its inherent joy, its unparalleled power, and the unique connection it offers with the Divine, while emphasizing that, though driven by the love innate to everyone, it requires the guidance of a spiritual master to master its practical details, from diet to meditation and directed study.

The Joy of Love in Bhakti-yoga

Bhakti-yoga is the yoga of love, making it the most joyful process of spiritual connection. In The 3T Path, I write that “devotion is powerful because it is an expression of your ability to love” and that “no ‘connection’ is more important than love.” Unlike views that associate spirituality with sacrifice or extreme austerity, bhakti-yoga celebrates life through loving surrender to God. Whether chanting Krishna’s holy names or offering food with gratitude, the practitioner experiences a spontaneous joy that springs from the heart. This path doesn’t demand rejection of material existence but redirects the soul’s natural love toward Krishna, “the all-attractive.” Thus, the practice becomes an act of divine pleasure, where every moment can be filled with the bliss (ananda) of being connected to the supreme source. Bhakti-yoga is, therefore, a journey of happiness, accessible to all who wish to live love in its purest form.

The Unparalleled Power of Love

Bhakti-yoga is also the most powerful of spiritual paths because it utilizes the mightiest force we possess: love. In the book, I state that “devotion will motivate you like nothing else” and that it is “the most powerful tool you have for transformation.” Love, present in each of us, transcends barriers and inspires resilience, becoming the engine of spiritual elevation. While jnana-yoga, with its focus on knowledge, is a natural and essential process that strengthens intelligence and wisdom, bhakti-yoga amplifies this progress by channeling love as a propelling force. The practice of japa—meditation with the Hare Krishna maha-mantra—exemplifies this: the transcendental sound purifies the mind and nourishes the soul, linking it to God’s infinite energy. I write that “in the path of yoga, [devotion] receives the highest importance and is repeatedly presented as necessary to maximize your full potential.” This power lies in love’s ability to transform not only the practitioner but also their relationship with the world, making bhakti-yoga a supreme path to realization.

The Most Intimate Connection with God

Bhakti-yoga provides the most intimate connection with God because it is grounded in love—the foundation of all personal and reciprocal relationships. In The 3T Path, I present Krishna as the “Supreme Personality of Godhead,” with whom the soul can cultivate a deeply affectionate bond. Unlike impersonal approaches, bhakti-yoga offers “the two-way path of love,” allowing one to experience “the five flavors of love”—from reverence to friendship and the most intimate affection. This relationship culminates in prema, pure spiritual love, which I describe as “the final and completely perfect state of existence.” Every act, such as offering one’s life to God, becomes a loving service that draws the soul closer to His transcendental abode. The 3T Method, with practices like chanting divine names and consuming prasada, reinforces this living, dynamic connection. Bhakti-yoga is not merely a means to liberation (moksha) but an eternal, loving union with Krishna, marked by the closeness and reciprocity that only love can provide.

The Need for a Spiritual Master

Though bhakti-yoga draws on love, a force natural to all, its full practice requires detailed guidance, and this is where a spiritual master becomes essential. In The 3T Path, I stress that “without a fixed daily practice, called sadhana, progress is very slow” and that “it is essential to choose a path and a primary spiritual instructor.” Love, however spontaneous, must be refined with discipline and wisdom to reach its fullest potential. The spiritual master guides the practitioner in practical aspects, such as mantra meditation (japa) with the japa-mala, preparing prasada with ethical food choices and the offering, and studying texts like the Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam. I write that “the grace of the spiritual master is knowledge,” but the student must apply these instructions earnestly. Without this guide, one risks getting lost in unstructured attempts, diluting bhakti-yoga’s transformative potency. The master is the link connecting the soul’s innate love to the structured method that leads to ultimate realization.

In summary, bhakti-yoga is the most joyful, powerful, and intimate path of spiritual connection because it is driven by love—a universal force that, when directed to Krishna, reveals our highest potential. Yet, to walk this path successfully, the guidance of a spiritual master is indispensable, providing the practices and knowledge that transform this love into a journey of self-realization. As I write in The 3T Path, “devotion is the key to success and the ultimate goal,” and with a trustworthy guide, this love leads us back home to Krishna’s eternal abode.